ABSTRACT

This article presents the experimental approach to the incidence of the sketch as an exploratory technique within collaborative design processes carried out asynchronously - distributed in global academic scenarios. Understanding the sketch as records loaded with semantic content that refer to the world where the designer lives and their interactions with others. And to the sketching as a process of transformation of thought powered by the dynamics of collaborative work and digital environments that allow remote work. The planning, structuring, development, and results of the international collaborative practice are documented for the fuzzy front-end phase of the design of a product, which involves the formation of teams about the profiles of the participants and the use of similar graphic representations. Sketch as a means of cohesion, documentation, and exploration for creative activity. The International Creative Workshop (ICW) was developed with design students from institutions in the cities of Hong Kong (SAR China), Monterrey, Bogota, and Cali.

Author Keywords:

Collaborative design, design drawings in development, industrial design, sketching, workshop drawing.

INTRODUCTION

Teamwork has been established as one of the main objectives of training in design programs, as the development teams of product in productive environments involve several designers who work from collaborative ways to respond according to the needs of the environment previously identified by the companies. This collaborative design practice is recurring in various latitudes and has been gaining strength in recent years due to the recognition of joint creative potentials and the market globalization that increasingly demands the multiplicity of perspectives in the development of the products. The initial phases of the design process depend heavily on the interaction of team participants and will be mediated by expression and communication techniques that facilitate reconciliation in the ideas, the argumentation of the decisions and the configurative exploration of the design products.

The landscape of design practice in global academic settings is characterized by the inclusion of collaborative strategies in the classroom where training approaches largely meet the expectations of the field of regional or local action, consistent with the development plans structured by the governments of each country. However, training strategies have been seen affected by the current communicative dynamics that are based on the information and communications technologies (ICT) situation that has expanded the range of digital tools implemented in the processes of the classroom.

The dynamic nature of design professionals implies the direct participation in the contexts and scenarios for which they are developed products, a situation that has expanded the potential of distance work (teleworking), a modality that is recognized by Colombian law in law 1221 of 2008. Design as part of the professions leveraged in the plans of national development in Colombia has not been indifferent to this situation and in recent years, the numbers of free Lance [1] based designers have increased your work in labor relations online. In the framework of the ways of interrelating participants of a communicative system that is carried out in a different moment and indifferent place it is called asynchronous distributed [2], therefore, The International Creative Workshop can be understood as a scenario for collaborative design asynchronous distributed.

The technical components of the design practice are very varied and closely match the objectives of each phase. For the initial phases of the design process in which less specificity and greater creative exploration are required, the most used tools are those of similar characteristics, while for the phases of productive technical development, technological resources such as those recommended are highlighted, understanding the practice of sketch as a highly sophisticated technology for creative problem solving [3]

This is how the sketch as a quick exploratory resource takes value in the activities of schematization of initial ideas and facilitates the creative processes of designers. Establishing a scenario of divergence through analog registration and allowing graphic interactions between participants. Collaborative design dynamics constitute an opportunity for management of knowledge from the practice of the profession and a relational laboratory of the predisposition of creative activities to scenarios of trans-disciplinary collaboration.

APPROACH AND PRODUCTION OF THE ICW INTERNATIONAL WORKSHOP

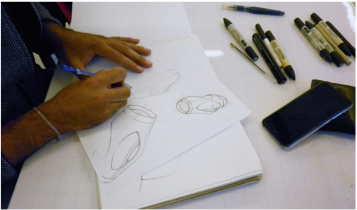

The complexity of design projects in a globalized world energized by information technologies and telecommunications provides a space for collaborative creation works, which tend to dilute the geographical, cultural and social boundaries that the political divisions have demarcated and that the economies have tried to sustain. This workshop emerges as an exercise to explore possibilities for collaborative-asynchronous work at a distance with groups of design students belonging to different cultures. The academic exercise experimental was proposed by Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano and Fundación Academia de Dibujo Profesional, institutions of higher education in Colombia that have design programs with a career greater than 40 years, extending it to peer institutions in the city of Monterrey, Mexico, and Hong Kong, China Linking countries that share cultural economic relations by the Pacific Ocean and that are promoting internationalization plans among themselves.

The implications of the International Creative Workshop in the field of design training required conceptual and methodological synchrony by the organizing team that reduced the geographical distance of the contexts and involved the creation of interactive environments, teaching approval, standardization of tools and alignment permanent objectives, supported by the use of resources supported in digital environments as tools for collaborative exploration focused on the use of the sketch and under the face-to-face tutoring of design educators.

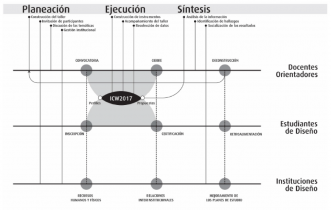

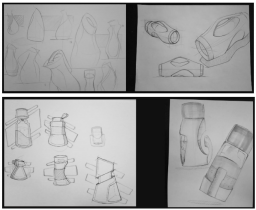

Under the title of “Sketching hot water bottles for cities,” a tribute to water was paid as the most important resource for the survival of humanity, attending to the felt need for preservation from the re-signification of the container from the cultural influences of each region.

The workshop exercises were focused to be developed in the initial stages of the design activity in design, where students and teachers as advisors must agree, through a negotiation process, on planning, structuring, and development of practice Situation that becomes more complex when agreeing with other cultures, a challenge posed from a language different from the native one, which for the interests of the exercise strengthens the formation of teams in relation to the profiles of the participants.

COLLABORATIVE DESIGN SKETCHING

For the purposes of the ICW workshop, the sketch is recognized as that set of unfinished, suggestive and open to reinterpretation semiotic records [4], which faces variables of incompleteness, assumptions and provisional decisions of the information [5]. With these records, it is intended to simulate on a two-dimensional surface, the depth and volume of a three-dimensional object. Specifically, the sketch In industrial design, it works as a means of representation adapted to creatively solve problems through rapid semiotic records, these drawings are part of the project planning [6] and allow the visualization of the idea to be shared with others and together make decisions about the next steps of the project activity.

The freehand sketch traditionally taught in design academies is individual in nature and takes place during the initial stages of the project process, where the cognitive activity is generated that precedes the materialization of the object. But the tools and context where the teaching of the sketch is done are apparently changing the technological tools, they will be an enhancer element in the future of the sketch made by more than one designer. There are two global investigations on the application of new technology for collaborative and remote sketching: The first one is in Belgium and is called SkeSha [7], a virtual desktop of Design created to work from an electronic surface with a suspended ceiling equipped with a double projection system that offers a large area and allows remote connections. And the second reference is from Canada and is developed at the University of Montreal at the Hybridlab Design Research Laboratory (Design through Research and Research through Design), the name of the system is Hyve-3D (Hybrid Virtual Environments 3D) implemented under the concept Sketch in 3D [8], to refer to a system developed with the intention of enhancing the experience of sketching between two or more distant locations, through an intuitive user interface based on the designer's natural body gestures.

In this scenario of emerging technologies applied to digital media interaction, the International Creative Workshop turns out to be a space that allows analyzing the role of the sketch as an analogous exploratory practice in international design environments, in its deployment as an evolutionary mechanism of registration and conceptual cohesion.

PROFILE IDENTIFICATION FOR COLLABORATIVE DESIGN

Collaborative design, also known as co-design, refers to the set of creative activities that involve two or more participants and whose central axis is configurative processes aimed at the material, strategic interventions or determinative actions of material culture. It has origins in the conception of participatory design [9], in which users are recognized as possible value contributors to the design process. However, this position referred more to an emerging field for design recognized by other authors under the designation of user-centered design [10], fine approaches to a broader concept understood as social design, in which the very existence of design is justified for the service of society [11], Klaus Krippendorf [12], understands design as a social activity in which users are actively involved.

Some theoretical approaches have attempted to define collaborative design as the set of co-creation activities that have a direct application through the design process [13], some other authors relate it to the set of activities that take place within the design teams [14]; [15] others such as Bucciarelli [16], defined the design as the result of a creative team based on the diversity of capacities and responsibility of its participants. All these theoretical positions independent of their nuances have a point of convergence: the idea of shared value, defined by Manzini [17], to refer to the benefit of the exchange of time, experiences and expertise.

Collaborative design practices have been popularizing in the last two decades with the rise of information and communications technologies, means with which the exchange of knowledge between participants takes place quickly, however, there is a close relationship which epistemically bases the design act [18], that is, the synthesis process of a culture that has in its social practice various manifestations of objectification.

Collaborative work is a way to strengthen capacities individual, promoting the multiplicity of perspectives and argumentative cohesion [19] and some authors have approached models to characterize this collaborative work in design activities [20]; [21]; [22]. Some research has attempted to approach the study of relational dynamics derived from collaborative creative design activities. The approaches are varied, and studies can be found from the transits of the information and the reflection of the action [23], studies on the types of collaboration [24], negotiation dynamics, evaluation criteria and roles [25], critical evaluations and hybridizations [26].

The collaborative design work is a practice in which collective creativity is enhanced from the exchange of knowledge, experiences, and competences of each participant. Looks like those of Amabile [27], Csikszentmihalyi [28], Wallas [29], and Talavera, Hurtado, Canto, & Martín [30] tend to understand the interactions of the participants that foster collective creativity from the roles, hierarchies, motivations, and dynamics that are created in the teams at the time of joining ideas and proposing proposals for solution.

Co-design teams must consider considerations related to profiles and roles that guarantee the expected quality of the results, including competencies and qualities for the strengthening of creative capacity [31], and therefore, it is essential to identify the appropriate people to participate in the stages suitable for the design project [32]. The International Creative Workshop is an opportunity to approach the study of the creation of design teams that allow demonstrating convergences and divergences in international comparisons from the competences of each participant, their ways of relating and the impact on the results obtained.

METHODOLOGY

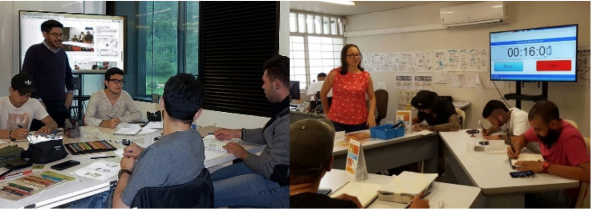

The realization of an international creative workshop with design students around the world, resulting in the development of design proposals on an environmental theme of global interest, requires the committed human capital that facilitates knowledge management and allocates time and resources to coordinate the processes related to logistics, teaching, and evaluation. For the International Creative Workshop, there were experienced design teachers, with research experience and who had interests in the practice of the students in charge.

The organizing committee of the International Creative Workshop was set up with a team of design professors who were in charge of the work sessions and were selected according to the relevance of the profiles and their research interests, which were subsequently linked to the proposal to be developed; its initial call was made through a formal request to participate on behalf of the related institutions. Professor Carolina Vesga attached by Academia de Dibujo Profesional, focused on the functions related to the usefulness of the product, specifically the design of the container, on the other hand, Professor Sofia Luna by Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León in Mexico was interested in the design processes and ways to solve problems; Likewise, Professor Camilo Angulo linked to the Universidad de Bogotá Jorge Tadeo Lozano arranged his attention on the evolutionary role of the sketch in stages of exploration and Professor Andres Roldan who was linked to the Hong Kong Design Institute in the city of Hong Kong focused on the creation of equipment for the practices of collaborative design.

The definitive link to the project must have had the institutional support through the approval of the leaders of the design departments or of the participating programs, who facilitated the spaces for the realization of the workshop.

The call to the participants as students for the workshop was made through an open call (Open Call), sending a digital invitation that specified information about the workshop and the participation mechanisms: title, language, dates, invited countries, requirements and a contact web address. Call to which the students responded accepting the didactics and proposed scope.

Prior to the call, the organizing committee held regular meetings through virtual work sessions in which the details of the workshop were discussed, defining objectives, themes, resources, means, scope and expected deliverables in accordance with the technical, economic possibilities and of time that limited each one of the linked countries. The theme “Sketching hot water bottles for cities” was chosen due to the relevance in the environment of the global problems, the level of development complexity in relation to the development time, the proximity to the study phenomenon and the expressive possibilities that allowed through analog drawing. The members of the organizing committee presented their ideas and agreed on tasks related to the stages of dissemination, execution, and evaluation of the international creative workshop.

INSTITUTIONAL MANAGEMENT

Due to the geographical distances between the 4 participating institutions, it was required to establish a schedule of precise times and conceptual rigor in the pretensions of the workshop, this to obtain the corresponding institutional guarantees that would give rise to the destination of educational spaces, resources, times and consents that allowed the logistic execution of the International Creative Workshop. Each of the linked design professors was responsible for the corresponding institutional arrangements and the obtaining of the permits to which it gave rise.

DEFINITION OF COMMUNICATION CHANNELS

The demands in communicative terms for the organizing team were met through instant messaging systems that offered the possibility of real-time reports of institutional administrative procedures, the socialization of information in virtual spaces, reducing the gaps generated by the schedule changes and leaving digital record of decisions made and setbacks presented. For the exchange of information, socialization of formats, bibliographic references and registration of activities and deliverables, multi-user cloud storage tools were available that allow simultaneous interaction. Likewise, for the conceptual cohesion, definition of didactics, construction of capture instruments and details, the use of a video call platform was sought after agreement of the work sessions. The communication channels were coordinated in advance of the workshop and were maintained during the months of information analysis.

RESOURCE APPROVAL

To obtain information of the best possible homologous quality for purposes of the comparative analysis between the 4 related institutions, it was necessary to establish applicable capture instruments in all learning environments, an analogous device was designed to allow evidence of different compositional relations of the proposals and that was standardized utilizing an explanatory video arranged on the internet that guided the materials and elaboration by the participants. Likewise, the requirements of the space for the execution of the workshop, the schedules and related didactics and the type of information available to the participants to have specific guidelines were provided about the handling of the sessions and the types of deliverables expected.

ANALYSIS

The international creative workshop had 22 students as participants, 4 guidance teachers, had 4 academic spaces in 4 different institutions of higher education, located in 4 different cities and 3 different countries with time differences of up to 13 hours; therefore, it required the approval of the capture and analysis instruments so that teachers members of the organizing committee and at the same time guiding the workshop obtained reliable, standardized and transparent information that would facilitate their subsequent analysis and discussion.

The pieces of evidence obtained were recorded in diverse media and provide information related to the profiles of the participants, the interaction with space, the analog resources used, the conceptual evolutions recorded through the sketch and the proposed design proposals. After the execution of the workshop, the information was centralized in a storage space virtual with free access of the guiding teachers, together with the analysis instruments built by the team.

DESCRIPTION OF THE CAPTURE INSTRUMENTS

The collected evidence focused on 4 different instruments, which vary in format from one another but were homologated by the guiding teachers in stages prior to the implementation of the workshop: (a) Form for profiling the participants, (b) Folding sketch, (c) Field diary and (d) Photographic record. The instruments, execution moments and technical requirements will be detailed below.

The Participant Profiling Form consists of a Google Forms® form arranged on the internet and sent by email to students composed of 23 multiple-choice questions and with an approximate duration for the completion of 20 minutes, with which it is intended to know through a self-assessment their design skills: communication, conceptualization, diversity of ideas, materialization, software management, relational skills, leadership, emotional control, autonomy, trend analysis, resource management, tool preferences, preferences in roles, abilities and skills and predisposition to teamwork. It is a tool implemented in moments prior to the execution of the international workshop and aimed to generate a profile of the participants according to their self-assessment.

The folding sketch is an analog resource built on parchment or tracing paper with which the different relationships of the proposed product are evidenced by graphic representations: structure, identification, expected functionality and interrelation with the user with a succession of superimposed and combinatorial graphics with the that the result was standardized in the four workshop execution environments. Its implementation was carried out during the execution of the workshop with subsequent systematization and the approval method was with an instructional video projected during the sessions. The implementation time of the capture instrument varied in a range of 20 minutes to 40 minutes according to the representative capabilities of each team.

Each of the guiding teachers kept a field diary in which notes were taken of the work dynamics observed in the sessions developed during the international creative workshop. Written descriptions record the interactions between participants and the student's reactions to the dynamics and resources involved. Each teacher had full freedom to verbally share the annotations with the other members of the organizing committee in subsequent virtual meetings.

As part of the visual evidence corresponding to the execution of the International Creative Workshop, a detailed photographic record of the sessions was kept, in which the use of space and the organization of an exploratory design environment, the disposition of resources and the relationships spaces of the participants and the guiding teachers. This information constitutes an important support at the moment of sharing the experience and concluding, roles, hierarchies, practical development and interrelational dynamics of the students.

DESCRIPTION OF THE ANALYSIS INSTRUMENTS

The analysis instruments used are classified into two objectives of interest: the first focused on graphic representations and the second, aimed at the creation of design teams based on the profiles of the participants. For the analysis of the graphic representation: The matrix of evaluation of the graphic expression has two units of analysis. First, what is related to the characteristics inherent in the collaborative sketching process, where five elements of the sketch making are highlighted in relation to its execution. According to Solano Andrade [33], several factors converge in decisions to give specific characteristics to their drawings. a) Definition: to refer to the ability to define a sketch and distinguish its elements, b) Promptness: is the ability to synthesize an idea in limited execution time and then incorporate more information, c) Size: is the ability to perform multiple small sketches and then a final one of larger size, d) Ambiguity: it is the transition of an imprecise development that goes to a clear and punctual one, e) Unfinished: where an incomplete set of elements is used to explain an idea.

Second, the analysis of types of lines from the graph. Understanding the lines of the sketch as a means to express a formal development of the collaborative design of a product, there are seven types of lines that can be distinguished [34]: a) Ghost: Initial set of very soft lines that are barely visible, that establish a footprint and allow experimenting, b) Outline: As a continuous and closed line that defines the external limits of an object. It is the thickest line of all, c) Profile: An artificial line that helps explain and visualize the shape. They are light, suggest the shape without indicating the real geometry and allow a three-dimensional reading, d) Technique: Dividing lines that join two parts of the mold or invisible union of two housings. They are a real edge in the product, e) Vignette: A partial frame intended to highlight a sketch on paper or screen, creating an illusion of depth, f) Emotional: These are lines capable of providing expression and urgency. They are lines drawn quickly and easily to add expressiveness, g.) Dithering: A series of lines that indicate the shadows cast on an object or those that the object projects and reinforce the depth.

FOR THE ANALYSIS OF THE CONFORMATION OF THE EQUIPMENT

Based on the initial findings of the exploratory study conducted with design departments in companies in Colombia, which was focused on the identification of criteria for the creation of collaborative design teams, four analysis units were established aimed at profiling participants: a ) Evaluation of skills in design activities, b) Preferences of design tools, c) Skills of designers, and d) approaches and orientations in the design project. These units were included in the participant profiling form, through multiple-choice questions about an online platform.

For the evaluation of skills in activities of design projects, a self-assessment procedure was sought, in which each participant assessed their skills against specific design activities on a qualitative scale of 5 levels and an additional option to express that some of them were not within their professional interests.

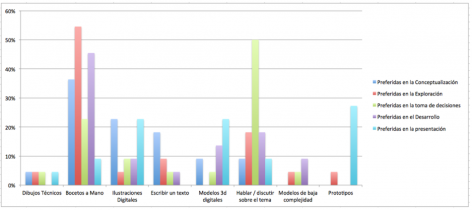

In the design tools preferences identification unit, 8 options related to means of expression related to design practice were formulated, some of which were identified by Pei, E., Campbell, IR, & Evans, MA [35], among which we could mention: technical drawing, hand sketches, digital illustrations, text writing, digital 3d models, talk / discuss the subject, low complexity physical models and prototypes; options that the participants selected for five specific moments of the design process: a) Conceptualization of design, b) Process of idea generation, c) Decision making, d) Development of proposals, d) Final presentation.

Likewise, to identify the abilities of the designers, the participants were asked to make a checklist with 11 skills and abilities (technical, attitudinal and management) that were mentioned by the department directors in the previous exploratory study.

Finally, the form allowed to gather information about the orientation in the design project (towards the details or the general panorama) and four possible approaches (ideas, processes, actions, relationships), which evidenced the claims of the participants.

The data of the participants were entered in the Codesign Match Tool test software that allows identifying, according to previous assessment of critical thinking skills, creativity and abstraction, the most convenient equipment according to the needs of the project, throwing work partners on a hierarchical scale. Information that is contrasted with the results weighting matrix completed by the authors against the proposals obtained by the workshop participants.

RESULTS

The experience of the International Creative Workshop was an exploration located in the participating design institutions of three different countries and does not intend to generalize the results obtained in its execution, however, after having verified the data obtained in the international creative workshop through of the capture instruments, apply the developed analysis instruments, review the results obtained and share through virtual sessions the details of the experience in each of the cities, the following findings have been identified:

Design students are oriented towards the details of the design project According to the information obtained, 64% of students prefer to focus on details, while only 36% work from a broad view of the project. From which it could be deduced that the look in many of the design schools focuses on the design profession as a practical exercise rather than as a strategic exercise. It should be noted that only one of the participating institutions showed a marked orientation towards the overall panorama of the project.

Design students prefer to work focused on the development of ideas. 74% of the participants in the international creative workshop expressed their interest in working on processes focused on the development of ideas, 16% prefer to focus on processes and 11% focus on relationships. It should be noted that none of the participants showed a preference for an approach towards action design, that is, towards the strategic activities of the project. The foregoing highlights the students' marked interest in creative design activities and divergent thinking processes.

Teamwork and the ability to draw by hand are the skills considered indispensable by design students. Just over 77% of the participants highlighted the importance of teamwork as an indispensable skill in designers, followed by hand drawing (72%) and the use of digital tools (68%). It should be noted that less than 10% of the participants mentioned writing clearly as an expected competition in designers.

Prototypes followed by illustrations and digital models are the preferred means of expression for the final presentation of the design proposals. 27% of the preferences expressed by the participants of the creative workshop said they mentioned the prototypes for the final presentation of their proposals, followed by digital illustrations with 23% and digital 3d models with 23%. At the opposite extreme, there are the media related to the writing of a text and the low complexity models that were not mentioned by any of the participants. The foregoing highlights the importance of functional models and digital media in the final phases of the design project. The hand sketch is the preferred tool for the process of developing ideas. 45% of the preferences of the students who participated in the international creative workshop chose hand sketches as the preferred means of expression for the development phase, followed by talking and discussing the topic (18%). Some media such as technical drawings and prototyping were not mentioned by any of the participants. The aforementioned strengthens the idea of the importance of analogical graphic expression for exploration but leaves a significant gap against the use of technical representation as a means of detailed proposals.

Talking and discussing the topic is the strategy preferred by students to make decisions about the design project. Half of the students consulted expressed their preference to speak and discuss the issue as the resource for decision making. A situation that reinforces the idea of the importance of collaborative work in the design process, by involving a diversity of perspectives, varied arguments and shared critical evaluation. It should be noted that none of them preferred the use of prototypes for decision making.

The sketch by hand stands out as the preferred means of expression for the exploration of ideas. Just over half of the participants (55%) expressed their preference for hand-drawing as the main means of expression when exploring ideas. Other media such as technical drawings, digital illustrations, and low complexity models had a minimum mention (5%) among the community consulted. The digital 3d models were not mentioned by any of the participants as a tool for the idea exploration phase.

Design students prefer hand sketches, digital illustrations and writing a text to conceptualize their design proposals. The use of sketches by hand with 36%, followed by digital illustrations with 23% and the writing of a text with 18% are the means of expression preferred by the students who participated in the international creative workshop at the time of conceptualizing Your projects and design proposals. The lowest participation was the low complexity models and prototypes with 0%.

The conceptualization, autonomy, and diversity of ideas of designers are the criteria that students highlight as strengths. In the self-assessment exercise, students highlighted their conceptualization skills (4.27), their autonomous work skills (4.18) and their abilities to propose diverse ideas (4.09). Likewise, the criteria that obtained the lowest qualification were those related to management activities (3.64), the skills for identifying trends (3.64) and the management of software tools (3.73). The self-perception of students who were linked to the international creative workshop is varied but is sustained in a range of just over one point, so that satisfaction could be deduced following their abilities, as well as recognition of deficiencies to improve.

Design students consider that it is not necessary for the construction of ghost lines as the basis for the sketch. Only (18%) of the participating groups explored in the sketch some very soft background lines that allowed them to establish some footprints as a framework for experimentation of the drawing, (36%) used very few lines with this form of construction, but in the remaining majority (46%) show a total absence of these constructive characteristics of the graph.

In the student sketches, they show the incorporation of some technical specifications necessary to be able to think about the technical design production. In the evaluation exercise on the expression of formal development, it was found that (27%) of the participating groups considered technical specifications for production in their sketches and (47%) of the groups incorporated some technical bases, only the remaining (27%) of the members did not give importance to this requirement or do not think about the possibility of materializing the idea at a productive level.

DISCUSSION

After a coordinated execution and obtaining the data of research interest proposed previously, it is necessary to share some appreciations about the experience in the aspects related to its approach and execution, to guarantee the replicability of the experience:

The students of the 4 institutions involved in the international workshop showed full willingness to participate in the inter-institutional exercise and expressed their interest in knowing the design processes and the type of results to the collaborative work that peer design students would obtain in their institutions originally. An incentive of interest lies in the exercise free of qualification and detached from related curricular activities in the courses of the plan; being voluntary participation, in an academic environment and without the pressure of any kind.

The use of freehand drawing as the main means of expression for the execution of the workshop was motivating as it allowed diversity in styles and techniques as well as a smaller investment of time and money; in the same way, the joint work sessions in institutional spaces established environments predisposed to graphic exploration, arranged with adequate resources and that stimulate dialogue among participants.

The accompaniment of the guiding teachers constituted the success of the experience as they support the activities to be carried out as academic practices of research interest, provide support in the use of the graphic expression as a means of evolutionary exploration and regulate the interaction spaces establishing norms, times, deliverables and objectives on the processes developed in the workshop. Likewise, the reflection from the point of view regarding the teaching of design about the implications that exist around the implementation of a new paradigm of remote representation is reflected in the felt need of teachers with a research profile motivated to foster analog practices and strengthen them through technological tools for drawing sketches, consolidating their experience and validating their permanent capacity for updating, expanding their understanding of spatial relationships.

The selected theme and the exploratory objective of the exercise implied a low level of complexity in the proposals, a situation that is adapted to the possibilities of the tools proposed for the workshop and the times and resources destined for the participants. In the same way, the construction of the sketch folding by the participants diminished the fear of failure and facilitated the appropriation of a useful graphic exploration tool. The total fulfillment of the deliverables, the fulfilled and complete attendance of the participants in the sessions and the interest in obtaining an official certification of their participation in the workshop are examples of an international creative workshop structured in line with the motivations of the design students in global scenarios.

The willingness of the Design Institutions involved to project their communities in global scenarios and allow them to know different ways of relating creative thinking with the means of representation is recognized, promoting collaborative work and establishing inter-institutional academic ties.

On the other hand, the comparative analysis of the results obtained allows the design processes to be homologated and the way they are conceived by the students in different training scenarios; The teachers involved facilitate the identification of competencies related to the means of expression, their relationship with the design activities, as well as the orientations and approaches of the training professional. The variations between profiles of the participant's present similarities in the use of resources, however, some aspects such as low interest in written expression, little focus on design actions and project orientation from the details give rise to a training profile that It has distanced itself from the strategic processes that concern the field of design.

Finally, the participants of this experience have expressed their interest in attending a new call in 2018 and contributing to the strengthening of inter-institutional networks through collaborative design practices that use the sketch as a graphic exploration mechanism.

CONCLUSION

The execution of the International Creative Workshop allowed the institutional approach of 4 design schools with different approaches, curricula, perspectives, and philosophies, around an exploratory practice of the sketch as an evolutionary registration mechanism in collaborative design processes. After documenting the results obtained, a marked understanding of design is identified as the proactive professional practice that responds to the needs of the environment through creative proposals materialized and visually expressed, foreseeing relationships with users, organizations, and environments. The collaborative design process is a practice that requires coordination, motivation, use of resources, permanent interaction and documentation of the results to achieve the proposed objectives. The environments, tools, and preferences of the participants constitute a potential for significant success.

Committed human capital is the key to the successful development of a creative international initiative such as ICW, due to the planning, management and execution requirements implied by the conceptual and methodological synchrony present in the academic practices derived from the proposed activities. The motivation and compliance of the participating students are found directly related to the credibility of the teachers guiding the workshop; in the same way that the motivation and commitment of the guidance teachers are based on the recognition of the potential of their students.

The distributed asynchronous environment proposed for the execution of the workshop allowed responsible use of information and communications technologies (online platforms, instant messaging systems, videoconferences, multiuser real-time editing files, and virtual spaces) as facilitators of the interactions supporting processes and without becoming the main medium dependent on the development of activities; Likewise, the analog and face-to-face practice boosted the interactions between guiding teachers and students within the framework of institutional spaces.

The design language is a catalyst for collaborative work allowing the interaction of team participants, conceptual coherence and procedural approval, is manifested with the use of the means of representation and is transversal to the phases of conceptualization, solution exploration, decision making, development and materialization of proposals.

The practice of the collaborative sketch during the ICW workshop, allowed to demonstrate the implementation of cognitive processes by the students, where their greater interest in developing the details of the drawing that the general panorama of the idea reduced the impact of strategic planning of the project of design. It is worth highlighting the preference expressed by the students in the preferred tools for the exploration and decision-making phases in the design project, with hand-drawn sketching being the most demanded due to the ease of being able to express ideas that can be quickly expressed share and on which they work in decision-making, from the drawing of a group of very specific lines, which allow a critical evaluation by others team members.

The design competencies in the linked institutions were evidenced during the execution of the workshop and recorded through the analysis of the results, in which the skills for collaborative work, design awareness as a complex thinking activity and a clear recognition of the relevant tools for each phase of the process are highlighted of design.

The next explorations of collaborative design based on sketching should expand the field of study to identify cultural variables of direct influence in the execution of the design process, the implementation of multi-user virtual environments, the compensation of competencies in virtualized teams and the possibility of generating synchronous spaces that facilitate interactions between participating students and guiding teachers in solving strategic design problems.

REFERENCES IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE

(1).Primer estudio de trabajo 3.0 de Colombia, MinTIC & MinTrabajo from http://www.teletrabajo.gov.co/622/articles-13905_archivo_pdf_resultados_2015.pdf

(2).Anumba, C., Ugwu, O. O., Newnham, L., & Thorpe, A. (2002). Collaborative design of structures using intelligent agents. Automation in Construction, 11(1), 89–103.

(3).Ledewitz, S. (1985). Models of design in studio teaching. Journal of Architectural Education, 38(2), 2–8.

(4).Tversky, B., & Suwa, M. (2009). Thinking with sketches.

(5).Stacey, M., & Eckert, C. (2003). Against ambiguity. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW), 12(2), 153–183.

(6).Castellanos, A., & Rodríguez, F. (2016). La gestion proyectual del diseno: aportes desde la comunicacion, el pensamiento visual y el pensamiento de diseno. Revista Kepes, 13(14), 206.

(7).Safin, S., & Leclercq, P. (2009). User studies of a sketch-based collaborative distant design solution in industrial context. In International Conference on Cooperative Design, Visualization and Engineering (pp. 117–124).

(8).Dorta, T., Kinayoglu, G., & Hoffmann, M. (2014). Hyve-3D: a new embodied interface for immersive collaborative 3D sketching. In ACM SIGGRAPH 2014 Studio (p. 37). ACM.

(9).Cross, N. (1972). Design participation: proceedings of the Design Research Society’s conference, Manchester, September 1971. Manchester, Inglaterra: Academy Editions.

(10). Norman, D. A., & Draper, S. W. (1986). User centered system design. Hillsdale, NJ, 1–2.

(11).Papanek, V., & Fuller, R. B. (1972). Design for the real world. Thames and Hudson, London.

(12).Krippendorff, K. (2005). The semantic turn: A new foundation for design. Boca Raton, FL: crc Press.

(13). Sanders, L., & Simons, G. (2009). A social vision for value co-creation in design. Open Source Business Resource, (December 2009). Recuperado de http://timreview.ca/article/310

(14).Erlhoff, M., & Marshall, T. (2008). Design dictionary: perspectives on design terminology. Basilea, Suiza: Walter de Gruyter.

(15).Kvan, T. (2000). Collaborative design: what is it? Automation in Construction, 9(4), 409–415.

(16).Bucciarelli, L. L. (2002). Between thought and object in engineering design. Design Studies, 23(3), 219–231.

(17).Manzini, E. (2015). Design, when everybody designs: An introduction to design for social innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

(18).Horta, A. (2012). Trazos poeticos sobre el diseño. Pensamiento y teoria. Manizales, Colombia: Universidad de Caldas.

(19).Schmidt, K. (1994). Modes and mechanisms of interaction in cooperative work. Risø National Laboratory, Roskilde, Denmark. Retrieved by https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kjeld_Schmidt/publication/257561154_Modes_and_Mechanisms_of_Interaction_in_Cooperative_Work_Outline_of_a_Conceptu...

(20).Mattelmäki, T., & otros. (2006). Design probes. Helsinki, Finlandia: Aalto University. Retrieved by https://aaltodoc.aalto.fi/handle/123456789/11829

(21).Sanders, E., Brandt, E., & Binder, T. (2010). A framework for organizing the tools and techniques of participatory design. In Proceedings of the 11th miennial participatory design conference (pp. 195–198). ACM. Retrieved by http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1900476

(22).Stappers, P. J., & Sanders, E. (2003). Generative tools for context mapping: tuning the tools. In Design and Emotion. Retrieved by https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=vBJqD22G2lkC&oi=fnd&pg=PA85&dq=Stappers,+P.+J.,+%26+Sanders,+E.+(2003).+Generative+tools+for+context+mapping:+tuning+the+tools.+In%C2%A0Design+and+Emotion.&ots=NoCsIEflT4&sig=4wTSgf0IJWPcRLzuth2AnxMQgr0

(23).Tang, H.-H., & Lee, Y.-Y. (2008). Using design paradigms to evaluate the collaborative design process of traditional and digital media. In Design Computing and Cognition’08 (pp. 439–456). Springer. Retrieved by http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1-4020-8728-8_23

(24).Maher, M. L., Paulini, M., & Murty, P. (2011). Scaling up: From individual design to collaborative design to collective design. In Design Computing and Cognition’10 (pp. 581–599). Springer. Retrieved by http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-007-0510-4_31

(25).Jin, Y., & Geslin, M. (2008). Roles of negotiation protocol and strategy in collaborative design. In Design Computing and Cognition’08 (pp. 491–510). Springer. Retrieved by http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-1- 4020-8728-8_26

(26).Nijstad, B. A., & De Dreu, C. K. (2002). Creativity and group innovation. Applied Psychology, 51(3), 400–406.

(27).Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 123–167.

(28).Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New Yprk: Harper Collins. Retrieved by http://www.bioenterprise.ca/docs/creativity-by-mihaly-csikszentmihalyi.pdf

(29).Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. Retrieved by http://doi.apa.org/psycinfo/1926-10372-000

(30).Talavera, M., Hurtado, A., Canto, J., & Martín, D. (2015). Valoracion de la creatividad grupal y barreras del pensamiento creativo en universitarios. Journal of Learning Styles, 8(15). Retrieved by http://learningstyles.uvu.edu/index.php/jls/article/view/224

(31).Von Stamm, B. (2008). Managing innovation, design and creativity. Chichester, Inglaterra: John Wiley & Sons. Retrieved by https://books.google.es/books?hl=es&lr=&id=IlC7bN94zWgC&oi=fnd&pg=PR11&dq=Von+Stamm,+B.+(2008).%C2%A0Managing+innovation,+design+and+creativity.+John+Wiley+%26+Sons.&ots=MPNcRQbLhK&sig=-IUzOdNVjx_1z3Nb12NSAsk9zDo

(32).Steen, M., Manschot, M. A. J., & De Koning, N. (2011). Benefits of co-design in service design projects. International Journal of Design 5 (2) 2011, 53-60. Retrieved by http://repository.tudelft.nl/view/ir/uuid:eefaaa3c-cc7d-408e-9e00-883c6f2ccb03/

(33).Solano, A. (2014). La ensenanza del boceto como objeto de diseno. Actas de Diseno, 8(16), 254.

(34).Henry, K. (2012). Dibujo para disenadores de producto: de la idea al papel. Promopress.

(35).Pei, E., Campbell, I. R., & Evans, M. A. (2010). Development of a tool for building shared representations among industrial designers and engineering designers. CoDesign, 6(3), 139–166.

LOS AUTORES:

Camilo Andres Angulo Valenzuela, Ph.D.

Universidad Jorge Tadeo Lozano

Bogota, Colombia

Andres Felipe Roldan García, Ph.D.

Universidad Nacional de Colombia

Sede Manizales

Manizales, Colombia